To behold the face of the other

/“Compassion asks us to go where it hurts, to enter into the places of pain, to share in brokenness, fear, confusion, and anguish. Compassion challenges us to cry out with those in misery, to mourn with those who are lonely, to weep with those in tears. Compassion requires us to be weak with the weak, vulnerable with the vulnerable, and powerless with the powerless. Compassion means full immersion in the condition of being human.” (Henri J.M. Nouwen)

“Compassion is not a relationship between the healer and the wounded. It's a relationship between equals. Only when we know our own darkness well can we be present with the darkness of others. Compassion becomes real when we recognize our shared humanity.” (Pema Chödrön)

“How much can we ever know about the love and pain in another heart? How much can we hope to understand those who have suffered deeper anguish, greater deprivation, and more crushing disappointments than we ourselves have known?” (Orhan Pamuk)

“Compassion alone stands apart from the continuous traffic between good and evil proceeding within us.” (Eric Hoffer)

“With the afflicted be afflicted in mind.” (Saint Isaac the Syrian)

There are words which not only sound deliciously beautiful [melliferous, cinnamon, tantalizing, felicity], but which also carry a deeper and more revealing resonance [nostalgia, astronomy, angelic, philosophy]. And then there are others, the same beautiful and resonant, which go even further. To reveal profound practical realities once broken free from their etymological shell [compassion, companion, communion, compunction]. Here I would like to stop on a word which if we should stay to consider it in all of its wonder and implication, would bring us to tears. This is probably my favourite word: compassion. Compassion from Middle English: via Old French from ecclesiastical Latin compassio(n- ), from compati ‘suffer with’. It is a “sympathetic consciousness of others' distress together with a desire to alleviate it.”[1]

Source: https://orthodoxartsjournal.org/st-peter-on-the-right-st-paul-on-the-left/

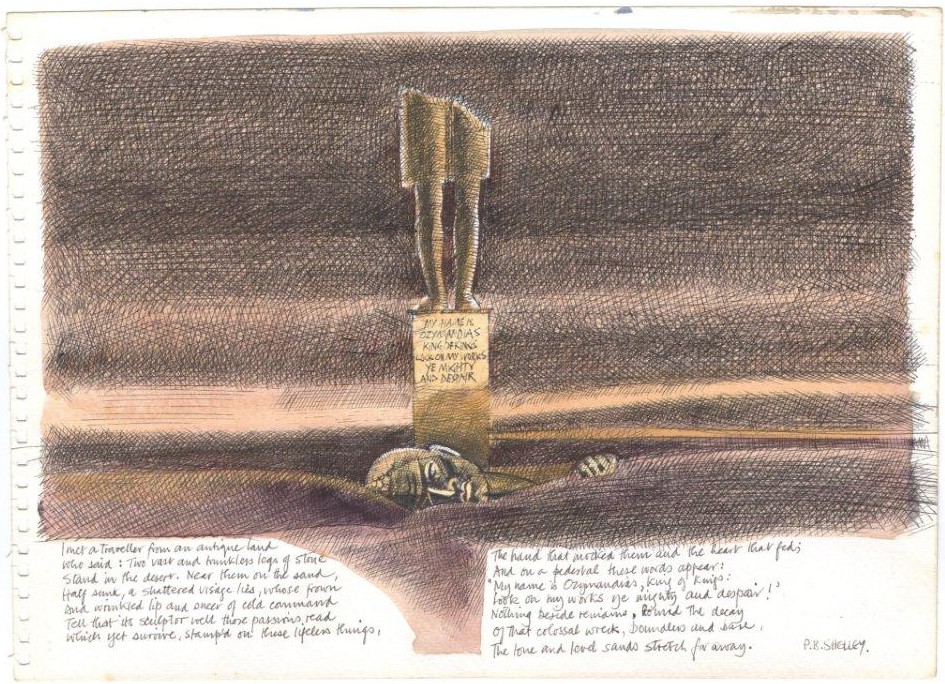

Love itself presupposes the movement of compassion for to begin with, love proceeds from a “strong affection”. If I have no compassion for you, then it stands to reason that my confession of love will not stand, it will not hold up. It would be like building a house on unstable ground. This is what the traditional words of the marriage vow: “[f]or better, for worse… in sickness and health”, are meant to convey. “Compassion is the greatest form of love humans have to offer” (Rachael Joy Scott). A truth which this inspirational young soul, who lost her life in Columbine far too soon, learnt early in her growing years. Love and compassion go hand in hand. I will stay with you, and if need be when that time arrives, I will share in your suffering and I will be there for you. I will co-suffer with you. I want for us to be part of each other’s redemption. To behold the face of the other. Like the heart-warming icon of the reconciliation of Saints Peter and Paul.

Compassion inspires hope, that feeling of trust and expectation, when everything around us might seem dark. We all do battle with our lives, oftentimes this battle is an inward one and it can frighten us to ‘conspire’ with harmful responses. Other times we cannot hide our sufferings and it is public for all to see, as was for example, the tribulation of the prophet Job. He was to ultimately through his steadfastness, experience both the compassion and the mercy of his Creator (Job 42:7-17). Those that love us will have compassion for us, they will extend their hand, put us in their embrace. They remind us of those good and vital things which we may well have forgotten, or which might now seem blunt. They give us hope and point us in the right direction.

“To be compassionate requires attention, insight, and engagement”, a religious has somewhere very well said. Even as the ‘leper priests’ did at the deepest level when they willingly entered into leper colonies to offer hope and succour to the suffering. We are no longer expected to do this, but let us think on this for a moment, we have become hesitant to even shake the other’s hand. Leo Buscaglia, the widely beloved philosopher and educator, reflecting on the meaning of life after the tragic loss of his student: “Too often we underestimate the power of a touch, a smile, a kind word, a listening ear, an honest compliment, or the smallest act of caring, all of which have the potential to turn a life around.” This “power of touch” has nowadays taken on a new meaning. Masks, gloves, and social distancing. People dying without holding the hand of a loved one. Never before have we realized the vitalness of the power of touch. And of the magnitude of compassion.

We have seen that one of the evidences of compassion is to let the other know you are there for them. To speak words of comfort and succour into their ear. Don’t tell them that you understand, because in all likelihood you don’t, but do tell them that your empathy is borne from your own life-experiences. Thirst is a stranger to none. Nor is despair. Sometimes, too, when we express compassion, we might at the same time have to give the ‘benefit of the doubt’, to hold back on any judgements. In Buddhism compassion requires prajna [transcendental wisdom], that is, an ability to get past the shallow appearances and to discern the true suffering and needs of the other. This is to go deeper, if at all possible, to practise “compassionate empathy” when we are “spontaneously moved to help”.[2] Mercy is normally associated to the giving of forgiveness, so there will be occasions when we could be called to practise compassion by forgiving those who have hurt us, when they might not have known better. “Jesus said, “Father, forgive them, for they do not know what they are doing” (Lk. 23:34).

There will be days when we are tired or overburdened, or indeed suffering ourselves. When we cannot be the support we would want to be. The additional weight might be too much for us to bear for the moment. Even here, we need to make use of our discernment. Milan Kundera, the Czech writer best known as the author of The Unbearable Lightness of Being has described this very honestly, “[f]or there is nothing heavier than compassion. Not even one's own pain weighs so heavy as the pain one feels with someone, for someone, a pain intensified by the imagination and prolonged by a hundred echoes.” What then? Do not feel guilty, for if you break down, you would be of no help to anyone. Emotional exhaustion [or even ‘pathological’ appropriation] is never a good thing. But try best you can, not to ignore the others cry, if you can. A letter. Or a card. Or an email. All this does help. And even if this is too difficult, then a prayer said with compassion, whatever the workings of prayer, is not lost. “But truly God has listened; he has attended to the voice of my prayer” (Ps. 66:19).

Many would be familiar with the Parable of the Good Samaritan one of the most beloved gospel stories from the New Testament (Lk. 10:25-37). The Samaritan at great risk to his own self, shows empathy and practises compassion to care for his Jewish neighbour who was beset by highway robbers and left to die. At the time the Samaritans and the Jews were at enmity one with the other. Others passed by the wounded and dying man and given their profession, you would have expected for them to stop. But they did not. They did not practise compassion. They kept going. But the good Samaritan stopped to give comfort and to care for his neighbour. He practised both compassion and mercy. And he was greatly commended by Christ that we might also follow in his example, “Go and do likewise” (Lk. 10:37). Compassion has no interest for race and is blind to the colour of my skin. It does not ask for my creed. It offers itself freely like a beatitude. Martin Luther King, Jr., loved this parable and made frequent use of it. He understood the road “from Jerusalem to Jericho” where the story unfolded as one which must be transformed so that true compassion is “not haphazard and superficial”. He knew too well that words devoid of truth are meaningless. So did the good Samaritan who did more than just “bandage” the wounds. Even the irascible Schopenhauer had recognized, "[c]ompassion is the basis of morality". It is a little more complicated than this long established aphorism, but it's truthful enough [3].

Why is it we naturally expect compassion for ourselves when at the same time we can often hold it back from others? This is a difficult question and it can challenge us. Only by looking deep into our hearts can we arrive at some answer, and even then, given any unpleasant discoveries, there remains the likelihood the response will not be entirely honest. We expect compassion because we are human and typically fragile. It is a healing balm. A medicine to the soul. “When we’re looking for compassion, we need someone who is deeply rooted, is able to bend and, most of all, embraces us for our strengths and struggles” writes the author of the Call to Courage, Brené Brown. There are times when we might hold back on this very same compassion, not because we are bad or wicked, no, but precisely because we are fragile and contradictory. Some could be normally suspicious, on account that practising compassion might mean giving the “benefit of the doubt” something which may possibly not come easy.

It will mean revealing the vulnerable side of ourselves at the same time. This could frighten us. And yet love, compassion, and vulnerability, are interlinked. Be certain on them, nothing in the world is more powerful or liberating. We have seen this manifested in history and in the lives of people time and again. It is the revelation to our hearts that we are not ‘existences’ in isolation one from the other. A universal idea so well synopsized by the well-known American Trappist monk, Thomas Merton, “[t]he whole idea of compassion is based on a keen awareness of the interdependence of all these living beings, which are all part of one another, and all involved in one another.” To love is to feel good, the heightened feeling of “communion” [from communionem, meaning "fellowship, mutual participation, or sharing."[4] To experience a profound pleasure in giving to the other. It is the same with the practice of compassion.

[1] https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/compassion

[2] http://www.danielgoleman.info/three-kinds-of-empathy-cognitive-emotional-compassionate/

[3] https://gophilosophy.wordpress.com/2014/06/18/compassion-is-the-basis-of-morality-schopenhaueressay-by-ivan-medenica