Eastern Orthodox Liturgical Chant

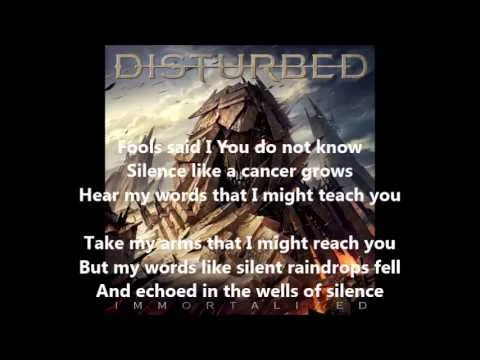

/Music has been a part of my life ever since I was a little child, a significant witness to the passing of the years. I can still remember. Whether it was listening to the Divine Liturgy, which Mother would play on her treasured vinyl records (LPs), or to the easy listening stations at the Reno Café, where the old Philips radio was forever on. And later by choice, when I was older, music would accompany me everywhere from the city across the ocean and into the desert. Whatever the condition of the heart, as King David one of the authors of the Psalms well knew, there is consolation in music. But I have even from my childhood noted a difference between what we might call sacred and secular music.[1] It seemed the natural distinction to make. And the manifest difference between the two? In very simple terms, sacred music relates to God, to ‘the divine’, whereas secular music will typically relate to the human, ‘to the earthly’. Sacred music as well, has a tradition of being accepted as a music genre set apart for worship by a large group of a believing community. It is conventionally in the form of a chant (“a rhythmic speaking or singing”).[2] Another difference between the sacred and the secular is that the former is text confirmed in scripture and liturgical texts, and does not stimulate or arouse violence or wickedness,[3] which secular music can do.

This is a tremendous topic and one which can stimulate much discussion, especially when it comes to definitions and to people’s biases of what actually constitutes the sacred.[4] It could be as difficult as trying to get behind Dostoyevsky’s enigmatic “[b]eauty will save the world” spoken by the Christ-like figure the epileptic Prince Myshkin. But technically, at least, chant, is one of the signature characteristics of sacred music together with its connection to ritual and cultic practices. I can be moved to tears, for example, when I listen to Kris Kristofferson’s country gospel “Why Me, Lord?”[5] Or Barbara Streisand’s haunting rendition of “Avinu Malkeinu”.[6] Where would musicologists place these songs in a canon of religious music? I know they swell up an enduring gratitude in my own heart. The spine-tingling Christos Anesti sung by Irene Papas [7] which was adapted by Vangelis from the traditional hymn is another piece of music which can test the boundaries for the definition of a music style or form. Nor as a Christian, is the magnificent Azan from Sheikh Abdul majeed,[8] or listening to Cantor Moishe Oysher,[9] something which does not deeply touch and act upon my spirit. Gregorian chant synonymous with the Roman Catholic Church plays a part in my devotions, as do the inspiring chants of the Taizé community. From the masters of classical music there is an impressive list of great requiems in the dramatic tradition of the concert oratorio. The purpose behind sacred music, or at least that music which is specifically set aside for worship, is to lead to interior reflection and spiritual growth.

“Nothing elevates the soul,” writes Saint John Chrysostom, “nothing gives it wings as a liturgical hymn does.” In modern terms this could be transliterated into Hunter S. Thompson’s poetics on music as “energy” and “fuel”.

The intention behind this little introduction was to share some paragons of the sacred music from my own community of worship, the Eastern Orthodox Church. Outwardly traceable to the classical age of the Greeks but strongly influenced by the “Jewish Synagogue chant and psalmody”, eastern liturgical chant in its present recognizable form was developed in the earliest years of the Byzantine Empire.[10] Below are samples of the chant which is not to be confused with the Byzantine music of the courtly ceremonials.[11] If you do not have time to listen to all the pieces, then might I suggest the cantor who is considered the principal of his generation, Theodoros Vasilikos, and the angelic Cherubic Hymn from the Novospassky Monastery Choir:

From left to right: Oikoumenical Chant, Cavarnos, Vasilikos, Pascha Hieron, Karantzi, Valaam Chant, Novospassky, Simonopetras, Simonopetras, Basso Profondo, Angelic Voice, Arabic Orthodox

[1] http://www.linktoliturgy.com/index.cfm?load=page&page=1787

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chant

[3] On the so-called ‘imprecatory Psalms’ of the OT see: http://www.theopedia.com/imprecatory-psalms

[4] http://thesacredarts.org/about.html

[5] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=veBR0aH54M0

[6] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0YONAP39jVE

[7] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AKwizUzyj0I

[8] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5glgAGGRApY

[9] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GokTUfo27Fc

[10] https://www.liturgica.com/html/litEOLit.jsp

[11] Egon Wellesz’ A history of Byzantine music and hymnography (1949) remains one of the most comprehensive studies on the subject: http://www.amazon.com/A-history-Byzantine-music-hymnography/dp/B0007ISNT