Michael Eldred on the Digital Age: Challenges for Today’s Thinking

/Available from Amazon.com here and other leading bookstores.

This is the second book published by M&K Press in the Technology and Society series. Book one with Bishop Kallistos Ware is available here.

Description

The description was written by Michael Eldred.

This little book takes on a series of questions posed by M.G. Michael and Katina Michael. The responses are not conclusive, but rather intended to make the profound challenges presented by the Digital Age visible. These include: How does consciousness differ from psyche? What is the relationship between Artificial Intelligence and the mind? How are visions of transhumanism to be assessed? Why is it important to distinguish between 'what' and 'who'? Who are we to become in the cyberworld? How do the cyberworld and the gainful game of capitalism intermesh? Are ubiquitous surveillance, Überveillance and the loss of privacy inevitable in the Digital Age? Are questions of ethics questions of power?

It is commonplace to say that today we are living in the Digital Age. This period is characterized by the advent of the cyberworld that is populated by bit-strings of data being processed by algorithms. Algorithms themselves are also nothing other than bit-strings composed of binary digits, i.e., zeroes and ones. The result is a third bit-string that triggers an effect either within the cyberworld or outside , in our old, familiar, physical world. The effect could be to send off an e-mail from one electronic server to the digital address of another, a receiving electronic server. Or it could be the command to launch a deadly missile into the sky. The elementary processing unit at the very core of the cyberworld is the Universal Turing Machine that has algorithms copulate with digital data to produce effective offspring. Such a machine does not exist anywhere as a real, physical thing but is 'merely' an idea, a mathematical idea that has turned out to be immensely powerful.

This idea of a cyberworld inhabited by Universal Turing Machines has materialized within a very few decades to make a digital world with which we have to contend every day. For the algorithms now rule our lives. They enable us to do many things, and prevent us just as much from doing other things. Wrongly coded algorithms can wreak havoc in people's lives. Other algorithms enable life-saving surgery to be performed with hitherto unknown precision. So is it just a matter of weighing up the pros and cons of what the cyberworld has to offer us? Or are we challenged to think more deeply about just what this cyberworld is and what is driving it?

Techniques and technologies have been known for millennia all over the world, but the idea of what technology is was interrogated by Greek philosophy. The very conception of what is understood in the West as knowledge is tied to and intimately interwoven with how the Greeks understood technology, the art of making things: A skilful power, the know-how, acts upon material to produce an effect. Technology is effective! This is seemingly a trivial observation hardly worth mentioning. But what seems trivial is the hallmark of philosophical questions that open up abysses for the mind to fathom. What lies hidden behind the idea of effective knowledge is the unbounded will to power over every conceivable kind of movement and change.

Is the cyberworld that is today increasingly encroaching upon and becoming a surrogate for the physical world in countless ways the consummation of this absolute, effective will to power over movement? Are the algorithms the digital encoding of an understanding of one sort of movement that is outsourced from our mind to the cyberworld to produce effects, to steer movements, for better or for worse? Are the algorithms the digitization of our logical understanding in which the logos itself has been encoded as a digital bit-string and now operates autonomously out there in the cyberworld, only seemingly still under our control?

Author Information

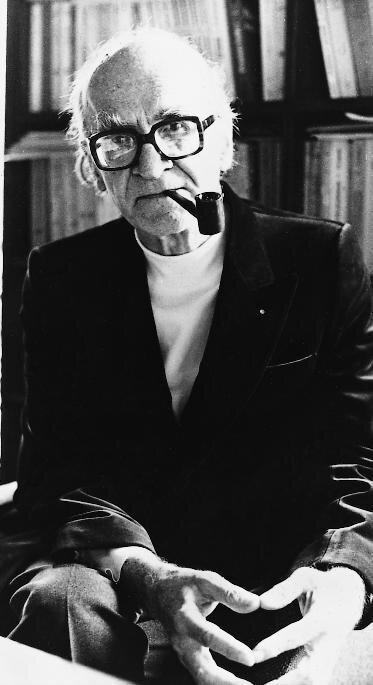

About the author:

Michael Eldred was born in 1952 in Katoomba and grew up in Leura and Katoomba in the Blue Mountains close to Sydney. He started studies in 1970 at the University of Sydney, first completing two science degrees majoring in mathematics, but including one year of philosophy. In 1975 he returned to philosophy, experiencing in 1976, through a visiting lecturer from Constance named Volkbert ‘Mike’ Roth, his introduction to the then-current, ongoing German discussion aiming at a critical reassessment and reconstruction of Marx’s encompassing project of a theory of bourgeois society. The debate had been triggered by Hans-Georg Backhaus, one of Adorno’s students, by a seminar paper Backhaus delivered in 1965. Marx himself had only ever completed multiple drafts for the first part of his six-part project under the title of Das Kapital: Kritik der politischen Ökonomie. He left behind not even completed drafts of his original plans for a comprehensive theory of the bourgeois ‘superstructure’. Eldred was awarded his PhD by the General Philosophy Department at Sydney University in 1984 with a dissertation on the reconstruction and extension of a form-analytic theory of capitalist society in a critical engagement especially with Marx and Hegel. Eldred was a tutor in both pure mathematics and philosophy at Sydney University and has taught courses at Constance University, the Pädagogische Hochschule in Munich, Witten-Herdecke University and for the Daseinsanalytische Gesellschaft in Zürich.

By translating Peter Sloterdijk’s Critique of Cynical Reason in 1984 for Minnesota U.P., he came across Heidegger’s Being and Time and phenomenology of the Heideggerian kind. This provided the impulse for intensive study of Heidegger’s writings that led him to the Greeks, especially Plato and Aristotle. Heidegger’s earlier lectures opened his eyes to how to read these seminal Western thinkers anew phenomenologically. Already at this time in the mid-1980s, he started a project on the question of whoness (a concept from Being and Time) in relation to an ontological gender difference between masculinity and femininity that resulted in two published books on masculine whoness in German. The interest in gender difference was a legacy of his time in General Philosophy, where feminism in the 1970s was a strong influence. By the early 2000s, the questioning of whoness had transformed into a wider socio-ontological inquiry, including questions of values as well as social and political power, and culminating in his Social Ontology of Whoness: Rethinking core phenomena of political philosophy (2019).

One of the major impulses for Eldred’s work has been to uncover the respective, quasi complementary, blind spots in Marx’s and Heidegger’s thinking, first published in 2000 in German and then in various editions, most recently in 2015, under the title Capital and Technology: Marx and Heidegger.

In 1990 he met the philosopher, Rafael Capurro, with whom he had e-mail correspondence in 1999 that developed the first scant outlines of a digital ontology. This intial exchange bore fruit as several articles and books by Eldred, most recently in his Movement and Time in the Cyberworld: Questioning the Digital Cast of Being (2019).

Eldred earned his livelihood from 1985 on as a freelance translator, gradually becoming specialized in contemporary-art catalogues. This occupation had the side-benefit of maintaining his independence from the rules of play in academic institutions and leaving him time for philosophical work.

He started playing guitar at the age of ten, which has accompanied him throughout his life. In recent years he has recorded several of his own philosophical songs (philorock) on a non-commercial basis and has also published a book on the phenomenology of music.

From a first marriage he has a daughter, Rachel Eldred, who lives in Sydney, and from a fateful encounter at a conference in Hamburg under the title Eros, Liebe, Sexus at the end of Septermber 1990, he has a philosopher-wife, Astrid Nettling, with whom he lives in Cologne.

About the editors:

MG Michael and Katina Michael have been formally collaborating on technology and society issues since 2002. MG Michael holds a PhD in theology and Katina Michael in information and communication technology. Together they hold eight degrees in a variety of disciplines including Philosophy, Linguistics, Ancient History, Law and National Security. MG Michael is formerly an honorary associate professor in the School of Computing and Information Technology at the University of Wollongong, and Katina Michael is a professor in the School for the Future of Innovation in Society at Arizona State University. Katina is the editor-in-chief of IEEE Transactions on Technology and Society, and senior editor of IEEE Consumer Electronics Magazine. Michael and Katina reside in the Illawarra region in Australia with their three children.

Publishing Details

Publication Date: August 20, 2021

ISBN/EAN13: 1741283388/978-1741283389

Page Count: 84

Binding Type: US Trade Paper

Trim Size: 5.5 x 0.19 x 8.5 inches

Language: English

Color: Full Color

Related Categories: Technology, Ethics, Society