“Compassion is born when we discover in the center of our own existence not only that God is God and man is man, but also that our neighbor is really our fellow man.” (Henri Nouwen)

Many times I would be humbled if not completely heartbroken by my pastoral experience and it was this practical expression of the priesthood which often gave meaning and dimension to my calling. It was an education into the human condition not taught in institutions of higher learning and only occasionally captured in literature dealing with loss and suffering. It is difficult, if not impossible to be taught compassion. It is like a naturally good singing voice, you either have it or you do not. To be confronted head-on with absolute loss, some of this sudden and violent, some of it slow and agonizing, was a fast and hard lesson into the reality of unfathomable pain and the dreadfulness of death.

The one thing I could not accept even from the start of my little ministry was the ‘pious’ response to death, and I did try hard to avoid it. I am sure, however, that even with the best intentions I was not always successful. It was above all painful to listen to indefensible nonsense when it involved the death of a child when the words came from the mouth of a priest who should have known better, “A. is now with God, the Lord needed another angel.” This is not the loving Creator of things both “seen and unseen” but little more than a cosmic psychopath. C.S. Lewis reflected with brutal honesty on the heavy grief of losing his beloved wife:

“It is hard to have patience with people who say ‘There is no death’ or ‘Death doesn’t matter.’ There is death. And whatever is matters. And whatever happens has consequences, and it and they are irrevocable and irreversible. You might as well say that birth doesn’t matter. I look up at the night sky. Is anything more certain than that in all those vast times and spaces, if I were allowed to search them, I should nowhere find her face, her voice, her touch? She died. She is dead. Is the word so difficult to learn?”[1]

Mother Maria of Paris writing agonizingly and yet without the abandonment of hope, after the death of her beloved child:

“Into the black, yawning grave fly all hopes, plans, habits, calculations and, above all, meaning: the meaning of life… Meaning has lost its meaning, and another incomprehensible Meaning has caused wings to grow at one’s back… And I think that anyone who has had this experience of eternity, if only once; who has understood the way he is going, if only once; who has seen the One who goes before him, if only once- such a person will find it hard to turn aside from this path: to him all comfort will seem ephemeral, all treasure valueless, all companions unnecessary, if amongst them he fails to see the One Companion, carrying his Cross.”[2]

It goes without saying, I do not hold the answer, but I have made some reasonable peace with the hard reality of loss both in the context of my own faith and in the discernible movement of transfiguring love.[3] Like many of us, I too have experienced profound loss, and like most of us, it has for a season come close to paralysing me. I have yet to completely come to grips with the passing away of one side of our entire family or my darling Katina’s four miscarriages. I spoke of ‘transfiguring’ love, for this has been the implication and consequence of Christ’s own death and how from that darkest day in our human history, came the greatest solace to the human race, that death is not the end.[4] But this belief founded in a religious faith does not exclude those who are not religious, for the underlying lesson, the ‘meaningfulness’ of the resurrection [even if we should only accept it as a metaphor] is that death does not mean inertia. It is a movement and a response [both for the living and dead] from one condition into an other. There is hope for a better tomorrow, and should we endure through the dark night, there will come a time when at least something of our suffering, will make some sense. As impossible as it is to accept when pain has no words, a time of solace will come. And this ‘dealing’ will arrive for each one of us differently, at a different time and in a different way. For suffering is almost always an intensely personal experience. Even if in the meantime our loss is to be redeemed no more than with our dignity in the face of an overwhelming blackness, and our refusal to be fully broken.

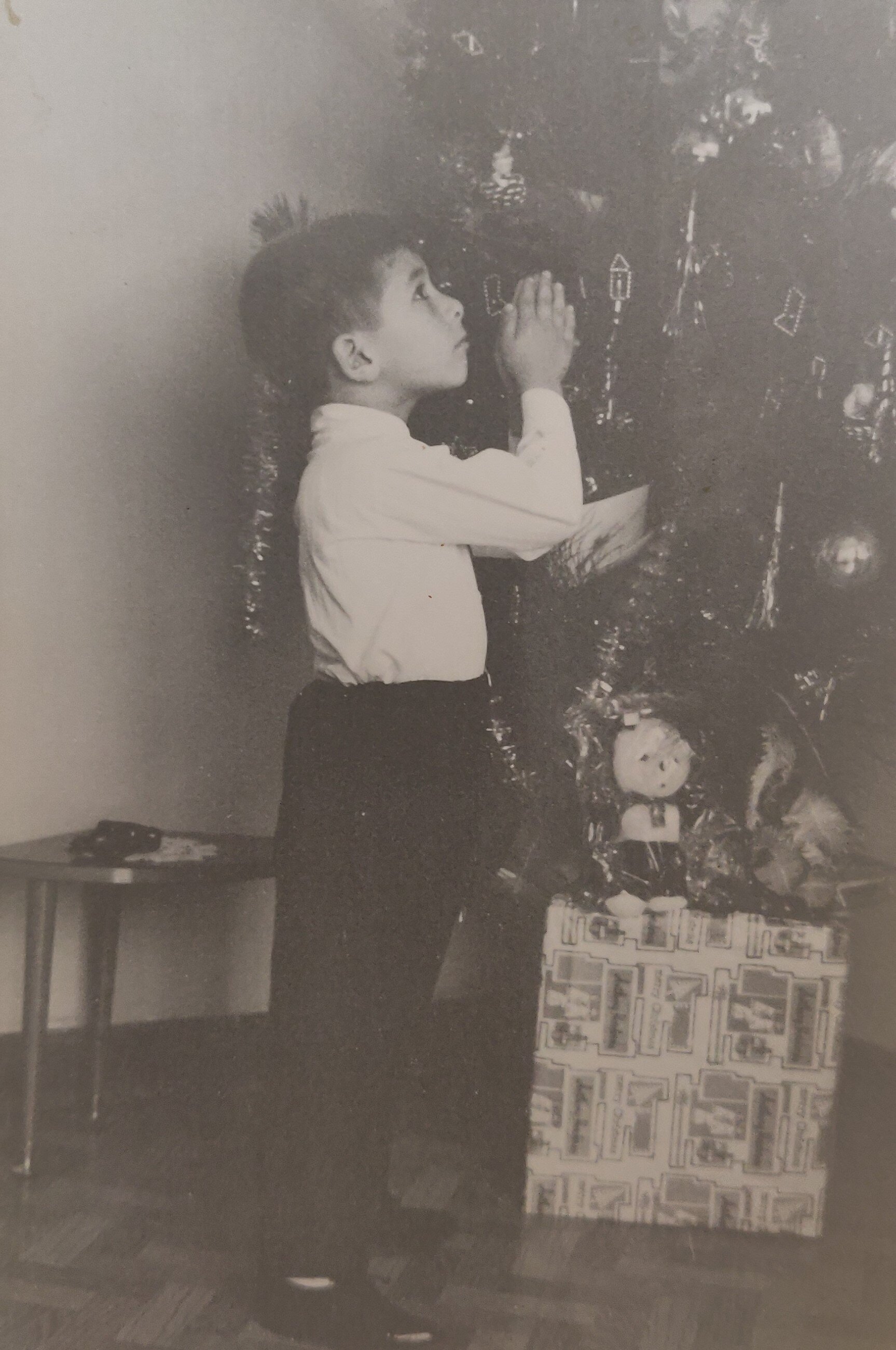

My brave young friend Leo

I have been blessed to have encountered genuinely courageous souls, amazed at the vast and often immeasurable endurance of the human spirit. Hospitals and grave-yards are the unadulterated universities of our world. It is in these places of unmistakeable reality we can measure ourselves and learn to heal and to forgive. I met Leo when I was still in the early stages of my ministry, starry-eyed and believing that I could make a difference. I would often make unannounced visits at hospitals and do not remember ever being turned away. In a pocket to my cassock I kept a carefully folded piece of white paper. On it I would register the names of all those I would visit and next to their name put down the colour of their eyes. There you are, I share with you one of my great secrets. We should look into each other’s eyes more often. It is all there, the unabridged history of a life.

Leo K., a young man in his early twenties had been involved in a horrific accident with the worst of all possible results: quadriplegia with locked-in syndrome [LIS]. He was fully conscious but trapped inside his body. Neither able to move nor to speak. A drunkard had disregarded a stop sign and crashed head-on into the beautiful boy who was riding his motor-cycle. The next time my brave young friend was to wake up it would be without movement in his limbs and without his voice. Until his death a few months later, he would only be able to communicate with his eyes. I would pray some silent prayers. Other times I would want to hold him in my arms. Did he like to dance? I am sad that was something I never had the chance to ask.

Leo and I would communicate using a magnetic board with red letters. I would point to a letter and he would blink at the right place. Then we would move on to the next one, soon we managed to work out short cuts and this made things simpler. So we were able to drift into other places and explore additional modes of communication. Not once did he complain or express a desire to die. Often he would be smiling. His heart was at peace. Of course, needless to say nothing of this was easy. It took titanic strength. Years later when horrifying thoughts of suicide would unrelentingly torment me, I would many times recollect him and hold back until the next day. I asked Leo if it was okay for me to bring a recording of the Gospel of John. He replied, “Y.” I asked him if he still believed. It was the same response, “Y”. There were other things we spoke about as well, including rugby league. He told me he was a fan of the Sydney Roosters. Leo, who had the most penetrating green eyes, died from pneumonia a few days before he was due to fly out to Moscow for some cutting-edge treatment.

One afternoon I visited Leo with a new seminarian. He said to me, “[w]e have nothing to complain about, look at Leo.” This especially upset me. We should not find comfort in the suffering of another nor look upon suffering with pity nor patronize the wounded. ‘Feeling sorry’ helps no one and can diminish our companion’s understanding of hopefulness. On some bowed stringed instruments we find metal strings, they vibrate in sympathy with the stopped strings. These are not touched with the fingers or the bow. They are called sympathetic strings. Compassion is something like that, to feel sorrow for the sufferings or misfortunes of another. Compassion [from the L. compati ‘suffer with’] has much in common with that glorious word: sympathy. What is sympathy? It is derived from the Greek sympάtheίa which literally means “feeling with another.” It is good to be a ‘sympathetic string’. Yet it is not always easy and it can only happen in small increments of grace like the baby steps we take to enter into the mystery of the parable of the Good Samaritan (Lk 10:25-37).

The Diving Bell and the Butterfly

At the conclusion of the last class when I was teaching regularly at the university, I would suggest a reading list to my students which was outside our information and communication technology (ICT) bibliography. This list included authors such as Primo Levi, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Viktor Frankl, and Jean-Dominique Bauby. JDB the editor of the French fashion magazine ELLE was made famous by his incredible book (which was published two days before he died), The Diving Bell and the Butterfly.[5] In 1995 at the age of 43 he suffered the brain stem stroke (the brain stem passes the brain’s motor commands to the body) which causes locked-in syndrome. Bauby with the help of some good people, particularly Claude Mendibil, wrote and edited his memoir one letter at a time with the only part of his body that he could still control… his left eyelid. He did this similarly to the way I would communicate with Leo, by using a board with letters. This type of system is often called partner assisted scanning (PAS). And like Leo, he too, would die of pneumonia.

[1] The Quotable Lewis, Wayne Martindale and Jerry Root (editors), (Tyndale House Publishers, Illinois, 1990), 149f.

[2] https://incommunion.org/2004/10/18/saint-of-the-open-door/

[3] ‘The paradox of suffering and evil,’ says Nicholas Berdyaev [whom Bishop Kallistos cites in The Orthodox Way], ‘is resolved in the experience of compassion and love.’ These oft quoted words point back to the Cross but also to Saint Paul who understands suffering as a participation in the mystery of Christ (Phil. 3:8-11).

[4] The Paschal homily of Saint John Chrysostom (c.349-407) read on the Sunday of the Resurrection continues to inspire and to comfort believers across Christendom: http://www.orthodoxchristian.info/pages/sermon.htm

[5] https://www.amazon.com/Diving-Bell-Butterfly-Memoir